This month I've had the good fortune of finding some great pages on the internet that I think my friends and readers* would find worth their time. We're going to start with those quick hits this time before we get to the longer writing below. You may recall the pattern for Septology this volume is that I'll write about a great book every issue; I got greedy this month and decided to write about three.

*all of my readers are my friends 🙂

First, three illustrations I found striking. The first one reminds me of the high modernism and associated posters I wrote about in Septology Volume 1, Issue 6: "We Have It All Figured Out And We're Serious This Time."

I often speak but rarely write about how my Grandpa Hatton was a highly respected employee of the Burlington Northern railroad; as such, I grew up with train memorabilia all around. Just now I searched "Wayne Hatton Burlington Northern" online and the second result, under his obituary, was a Montana legislative record with an eloquent testimony he gave (pages 12-19)—there was a law on the books about railroads being required to have agents in every town over 1,000 people, and it was up for debate. He uses the word "albatross" twice.

When we were up for his funeral this summer, my grandma had scrapbooks out about his career, and there was a news clipping about this same bill: "Hatton said the railroad simply cannot afford any longer to 'keep a guy employed just to make the coffee and be a Boy Scout leader.'"

The Hattons love trains. There's a famous family story where one night around the dinner table, my sister Cate, in third or fourth grade, knew off the top of her head that the standard gauge-width of train tracks was four feet eight and one half inches. Why do you know that, Cate? It was the width of the wheels of Roman chariots. (She was right.)

Our history provides a very reasonable and neurotypical justification for my interest in the railroad, but Becky often says that saying someone is "a fan of trains" sounds like a euphemism for being autistic. I've always thought that's funny. "Is he...you know..."

You're reading an archived copy of Septology. Sign up to receive the next issue right to your e-mail:

The second illustration is a placeholder from a New York magazine landing page, and I thought it was charming. I love sitting at the computer and looking out the window with a coffee.

The third comes from Computer Lib/Dream Machines, a 1974 zine that is historically considered the first book about the personal computer.

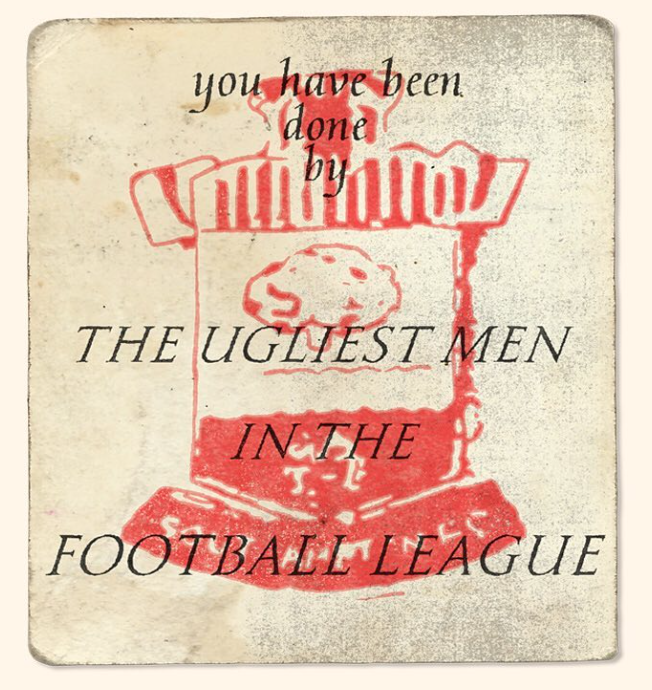

Also on the subject of beautiful images: I knew that from about the 1970s through the 90s, soccer fans formed violent street gangs to support their teams, but I did not know how organized they were, nor how funny. Many of the groups called themselves "firms," and went so far as to print up business cards. They would distribute these cards to individuals that they beat the crap out of.

"Hoolicards" has collected and printed several (including in a book, which, I've got a birthday coming up)

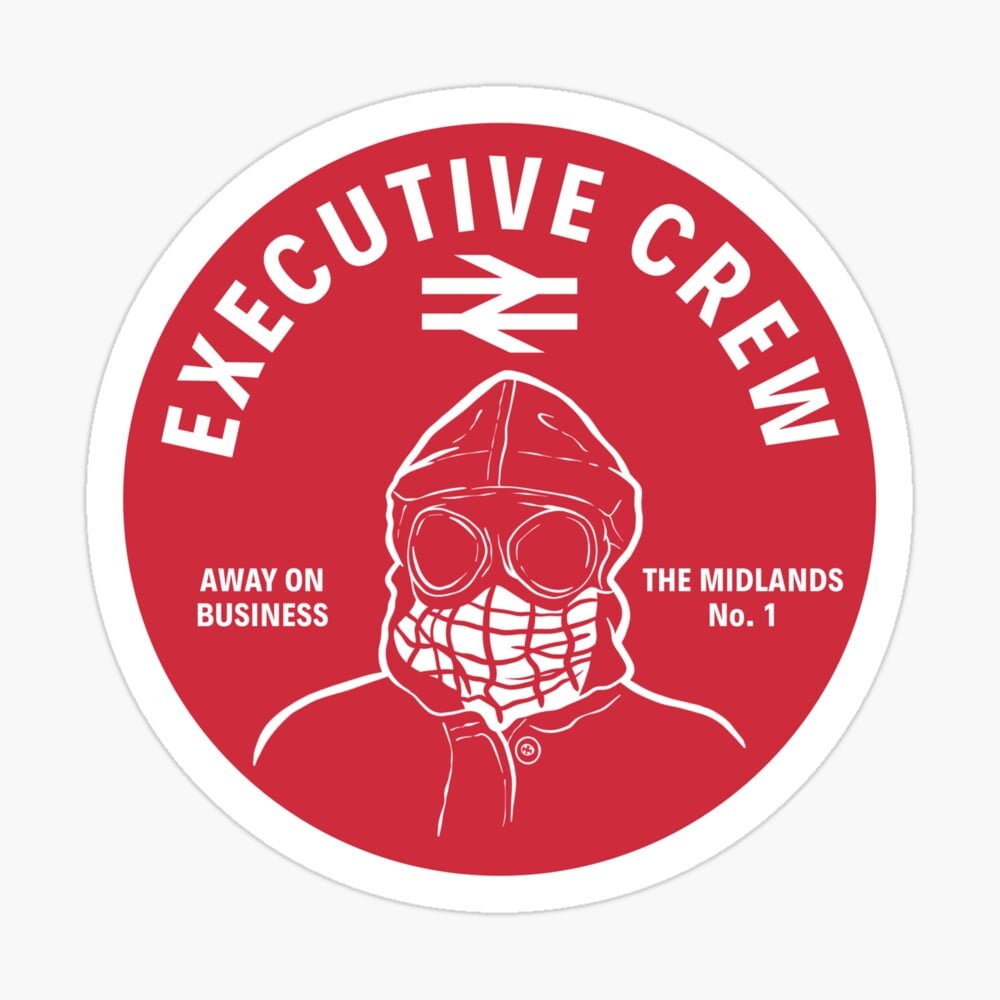

Some of the hooligans took the business facade a step further and gave themselves highfalutin names like "The Stockport Stock Exchange Pension Fund." The group associated with my beloved Nottingham Forest were one of these: they named themselves the "Forest Executive Crew."

The designs are sick and you can buy them on shirts from someone on Redbubble. I don't think it's worth it, though, because Forest was founded 160 years ago and it has rivalries over a century old—I don't want to get my ass kicked by Derby County FC's "Derby Lunatic Fringe."

Also in the Premiership: the Guardian's food critic went to a restaurant called "Brasserie Constance" in west London but did not know that it was in the particular corner of west London where Fulham play. The restaurant was in fact within Craven Cottage, which is the name of Fulham's stadium.

On a weekday, without a game on, the restaurant was open but deserted. Recognizing the food critic from the Guardian, though, someone decided to get some bodies in there right away for appearances, so, like, the entire Fulham marketing team came down from their offices to have large, loud lunches with barely any food on their table. Fun read.

Last one from England. A newsletter series I follow called "The Monday Media Diet" asks people what they read and consume; in an edition a few weeks ago, one guy said that he reads British High Court Judgments, because they are "remarkably well written—cool, brisk, and analytical...professionally, I use their clarity and structure as the model for my consultancy work." Cool idea! He also said they are often wryly funny, and the £24.3 verdict in Paul McCartney's 2008 divorce from Heather Mills is a classic example. So I read it, all 31,000 words, and did in fact enjoy it very much. It was technical but clean and smooth, very consistent and logical, not a winding tunnel of precedent and jargon. If you've got a free afternoon and that sounds interesting, I recommend it.

That took me a long time to read, but it pales in comparison to the personal library of Cormac McCarthy, which contains over 20,000 volumes. McCarthy didn't really make any money until he was about 60, at which point (after movie deals for All The Pretty Horses, The Road, and No Country for Old Men) he seems to have bought everything that caught his interest, including cars, guns, cowboy boots, and hundreds of unworn tweed jackets. And so many books. But as far as people can tell, he read them: books on Mesoamerican archeology and Charles Dickens, on F1 racing and the naked mole-rat, how to rifle your own gun, The Life of Saint Teresa of Ávila by Herself, Realism in Mathematics, books on needlework and quilting, and 142 volumes by or about Ludwig Wittgenstein.

A team of volunteers is trying to catalog it but it's taking them a long time. Smithsonian magazine ran a great piece about the library and its volunteers. Logging all of his annotations is what's taking the archivists so long—we know he read so many of his books because he did so with a pencil in hand.

Speaking of literary Texans and their libraries, that piece reminded me of the time I learned, a few years ago, that Chip Gaines, from the Fixer-Upper/Magnolia empire, had purchased Larry McMurtry's entire book collection after McMurtry's passing in 2021. That's a fun fact I like to wedge into conversation whenever possible. It was easier this spring when I was reading Lonesome Dove and talking about McMurtry in my day-to-day life more often.

McMurtry, remarkably, had about 15 times more books than McCarthy did—300,000 books, compared to 20,000. Most of that can be attributed to the fact that his collection was intermingled with the inventory of his bookstore, which he founded in Washington, DC, before moving it back out to Archer City, Texas. (Rent was cheaper in the panhandle than in Georgetown, I guess.) Incredible how many books old guys in West Texas can buy if they really set their mind to it and also they have Hollywood movie-rights money. Funny that it's happened twice so famously within the last half-decade.

Cormac McCarthy wrote his novels on an Olivetti Lettera 32 typewriter. Larry McMurtry wrote his on one of 14 Hermes 3000 typewriters, which he thanked in his acceptance speech at the Golden Globes after winning Best Screenplay for Brokeback Mountain. I write Septology on the computer. Usually I start in the TextEdit app and save sections as .txt files, and once I have the bare-bones text, I move it over to Buttondown or the web page or whatever it is. It's also my daily driver for one-off captions or social posts or even whole blog posts I write for work. Sometimes you just want to jot something down.

The advantage of TextEdit (like a typewriter) is its simplicity, and Kyle Chayka at the New Yorker wrote a column about how nice that is, a word processor that does not change all the time, that is not trying to AI you or make you log in with a passkey. (As a side note, Sheon Han at Wired made the case for "software criticism" on par with film or food criticism in 2023, because software is something we consume all the time and we should be clear on its advantages and disadvantages. Chayka's column is a good example of this.)

Kyle Chayka is probably best known for his 2024 book Filterworld, which is about "how algorithms flattened culture"—i.e., we don't decide what music we listen to, Spotify does. The idea of "AirSpace" which he coined and which I referenced last issue, is part of this, because we've all designed our apartments based on the same apartments we see on Instagram. The most convincing argument against the ideas of Filterworld would be that, look, man, I think you're an upwardly-mobile late-30s American man in a big city with a fair degree of disposable income, and a lot of people just have the same taste as you. Trends do not imply coercion or conspiracy.

Ironically, then, Chayka's argument in favor of TextEdit is an argument against algorithms flattening culture. I use and like TextEdit but not because it was recommended to me; in fact, as he makes clear, it lacks many of the heavily-marketed features that would make it susceptible to recommendation in the first place. It makes Apple no money. The fact that he and I both use it, then, only indicates that we're similar guys with similar priorities. There's nothing wrong with that. Nobody causing it, either.

If TextEdit is one of the tools that I use to create Septology, then so is my computer, and it logically follows that so is my mouse, and perhaps even my mousepad. That would be unremarkable most months, but this time I have mouse and mousepad updates to share.

I read the following in a newsletter (Installer from The Verge, which recommends stuff): "Everybody you know who cares about their computer mouse probably has an MX Master. And with good reason!" Oh? I thought. Could my computer experience be improved with a better mouse? It had never occurred to me before. The Logitech MX Master was in the news because its latest update, version 4, had just come out, but I looked it up and an MX 2 was on sale for half off, I could pick it up that very day at Target. It has a bunch of extra features, like a volume spin-wheel and buttons to go forward and back. It's nice! And since I'm at the computer all day, a small improvement to something I touch hundreds of times a day is actually a pretty big improvement.

The new MX Master 4 is $120 and the one I got was $60, which puts it in good Christmas gift range, especially because it is a gift that many people would enjoy and use every day but that relatively few would think to buy for themselves.

Two days after I bought my new mouse, I was at the thrift store and saw a gaming mousepad for sale. I looked it up—the "Corsair MM600"—and I cannot find it in stock online but apparently it retailed for around $60 before it was discontinued several years ago. It was $6 at the thrift store, so I bought it, of course. It was kind of a "if you give a mouse a cookie" situation, in which I was the mouse and the mouse was the cookie.

When I was in the office a few weeks ago, I was sharing my screen and swiping between windows and my friend and coworker Laurel said "It seems like you're someone who really knows how to use your Mac," and I was proud of that, I thought that was a kind thing to say. If I'm going to be using the computer anyway, might as well do a good job.

Last thing before we get to the books. In yet another newsletter, Scope of Work, I read the phrase "One memorable essay in my mental files of HVAC essays," which was like candy to me: I love reading highly specialized expertise in a broadly accessible piece of writing. There were three essays in the file: "The future of urban housing is energy-efficient refrigerators" in the MIT Technology Review, "After Comfort" in e-flux, and "Lies, Damned Lies, and Manometer Readings," in Asterisk.

I don't have or even really want a mental file of HVAC essays, but it's an example of the kind of curiosity and attention I want to cultivate, which I've prioritized in Septology. There are two things that I think are really fun about writing this newsletter: the first is saying "I saw this, and it reminded me of that." I love the connections. The second is working out my ideas on paper; often it is through the process of writing that the thinking happens. That's where the essays about books come in.

I'll keep these brief (under 300 words), because the e-mail already has plenty going on and because it will help me focus my thoughts. The three books are The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel, and Babel by R.F. Kuang. All excellent.

I finished Monte Cristo this morning before work, to be entirely honest with you. Last issue I wrote about how the Count of Monte Cristo ceased to exist as a person and instead chose to exist as a disembodied spirit of vengeance; I said I was "Excited to see if this theory holds up. You'll know a month from today."

It held up! At one point one character comes to him and says (I'm paraphrasing), "Monte Cristo, I'm scared of something: everyone who lives at M. Villefort's house is being killed by poison." The count responds, in essence, "haha that's wild maximilian I can't even believe it! Sounds like an agent of God's providence is probably killing those people on purpose and you probably should stay out of it I guess??? Yeah I would say stay out of it haha crazy tho"

Here's the problem I had with this book: the beginning was very exciting, the end was very exciting, the middle was 700 pages and tough. Tucker read last month's newsletter, written when I was two-thirds through, and said to me "this sounds like a man who does not like The Count of Monte Cristo very much." The good news is that I like it very much now, because the ending was great! But maybe I should have just read the abridged version.

Putting it down, I feel two things. First, I feel very fond of the characters, because by this point we've spent so much time together that they feel like friends, strange as they are. Second, and more deeply, I feel incredible warmth for the people I love who love this book and recommended it to me. Thank you for inviting me to join you in this.

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel is post-apocalyptic—a global pandemic has decimated the population, and we follow a band of survivors and also several overlapping narratives from before the collapse and after.

Becky asked if it was scary. I don't think so. Most of the suspense is built through making connections, rather than ratcheting up the danger. Like, we know that Clark gave Arthur a paperweight, and Miranda took it from Arthur, but for most of the book Kirsten has the paperweight, and then eventually she gives it back to Clark. So the exciting and interesting question is how does Kirsten get the paperweight from Miranda? (Miranda died twenty years ago!) The story is revealed more than it unfolds.

This makes it a very rewarding re-read. Without worrying about whether or not the pieces will eventually fall into place, reading it feels like moving slowly over the puzzle as it's under construction, admiring the picture and appreciating the craft and care that went into the connections.

The vision of the post-apocalypse that Mandel gives us isn't about how scary a post-pandemic future would be, but rather how beautiful this present is now. It is a novel deeply in love with the world. Everyone looks back with such tenderness on the telephone—it let you hear the voices of the people you loved even if they were miles away. You had little computers on which you could look up anything from history, or how the refrigerator worked, and learn all about it. You had machines that blew cool air in the summers. What a wonderful way to live.

(Miranda gave the paperweight back to Arthur, then he gave it to Tanya, actually, of all people, and Kirsten stole it from her.)

Babel by R.F. Kuang stands on the shoulders of giants; set at Oxford, there are elements of Narnia and Hogwarts in how our protagonist Robin was swept away from his Chinese childhood into a world of British academia and magic. The Translation Institute at Oxford is infused with magic that can be harnessed through making translations, and manifesting what's lost in translation.

This means Babel is a book about language, we spend a lot of time thinking about translations and etymology, which is exciting for me as a writer, and it also enables some very moving moments—when one character offers a well-placed "God be with you," toward the end of the book we know he's saying goodbye.

Robin and his friends are told that translation is a tool of peace, but this is the British Empire in the 1840s, peace is not Her Majesty's highest priority. Oxford is being paid to provide magical translations for the Royal Navy and the East India Company. This is most pressing for Robin, because Britain is trying to start the Opium Wars with China. As a translator, he and his friends create technology crucial to the nascent military-industrial complex—so what does that mean for them? How responsible are they for the colonizing applications of their labor? What can they do about it?

Interesting though they are, I wouldn't necessarily have picked up a book about those questions, you know? But what Kuang does, brilliantly, is transmit them through a propulsive, plot-driven novel, rather than literary navel-gazing. It's a story for grown-ups, but it's still a story—we have secret meetings arranged by secret codes, big country houses and grimy pubs, faked deaths, and eavesdropping from the top of the stairs. I loved it. I'm excited to read it again.

That's all for this month. We'll meet back here December 7 (a Sunday) for the last newsletter of this season. Thank you, as always, for reading.

From Dallas,

Tim