Good evening. I apologize if this seems rushed. I thought the 7th was tomorrow.

Table of Contents

Gilead by Marilynne Robinson is my favorite novel. Whenever I read Station Eleven (which I did last month) I think "oh...this might actually be my favorite..." but then I read Gilead again and I think "oh alright no this is the one." That's the book under discussion for this issue of Septology—the last edition in Volume 2.

I find myself talking about Gilead a fair amount, because when people find out I'm a writer, they often ask me what my favorite book is.1 When I tell them, I also tend to include the disclaimer that my dad was a pastor in Iowa, just like the narrator of the book is a pastor in Iowa, writing to his son.

As a general rule, I like leaving people to their own tastes and minimizing the amount of pressure I put on them to like the same things I like. I love saying "It's not for me," about something I dislike, because saying "it's bad" closes the door too hard—what if I say that to someone who likes it? By claiming a special connection to this novel, by means of its similarity to my own life, I offer a way out if someone doesn't like it, or don't find the premise interesting. It may not be for you, but it is absolutely for me.

You're reading an archived copy of Septology. Sign up to receive the next issue right to your e-mail:

The other thing I've often said about Gilead is that it doesn't have much plot—but re-reading it these past few weeks, I'm less certain. John Ames, the narrator, is in his eighties while his son is about six or seven, and he wants to tell the boy everything he would have gotten the chance to say if they were given more time together. This gives it a journal-like quality that at first seems to avoid any sense of rising and falling action. But this time, two distinct plots became clear to me, and in fact they are two of the most fundamental stories that are told: first, here's how we got here, and second, a stranger comes to town.

The second part of the book is mostly about what happens when Jack comes home. Jack is the son of Ames' best friend, and is in fact named after the old pastor, his full name is John Ames Boughton. He's been smart and mean his whole life, very much a Prodigal Son, but in Gilead, unlike Luke 15, we get to spend more time exploring how crushing it is for the people who love the boy to see him be so needlessly, deliberately, cruelly selfish. They forgive him and he takes advantage of them again. And now he's back.

That's the second part. The first part is the origin story of Ames' family, which is what prompts him to write to his son in the first place. Ames' grandfather was a John Brown type of figure, wild-eyed and full of righteous fury, and was in fact Brown's ally in Bloody Kansas. He used to fire into the air to gather the congregation together Sunday morning, and then in his sermon he would rile them up into enlisting in the Civil War. His son, Ames' father, inherited a church of widows.

John Ames and his brother Edward grew up in a house defined by tension between their pacifist preacher father and zealot preacher grandfather. And that's where we get most of our drama in the first act of Gilead, unwinding the grandfather's legacy and how it affects the generations to come.

But I was drawn more to Edward this time around. Edward was the beloved elder son, and the church passed the plate around to send him to university in Germany, but he came back an atheist. This would have been in the 1880s or 90s, and in the Nietzschean fashion of the day, he grew a big mustache and walked with a huge cane when he came back to Iowa (at like 23 years old). This of course led to a falling out between Edward and his father, with his little brother John caught between them.

John writes about how Edward gave him The Essence of Christianity by Ludwig Feuerbach, who was a famous atheist, "thinking to shock me out of my uncritical piety." Edward also told him "John, you might as well know now what you're sure to learn sometime. This is a backwater—you must be aware of that already. Leaving here is like waking from a trance." But he doesn't. John stays in Gilead. In his narration, he's a little self-conscious about it. Edwards goes off to Lawrence, Kansas, to teach German literature at the university, but he remains as a devil on his little brother's shoulder, questioning the faith that is Ames' whole life.

On the one hand, that's been helpful: "I believe I have tried never to say anything Edward would have found callow or naive," Ames writes. "That constraint has been useful to me, in my opinion…There is a tendency among some religious people even to invite ridicule and to bring down on themselves an intellectual contempt which seems to me in some cases justified." When Jack returns to town, this philosophical rigor takes on renewed importance, because the younger man is looking for somebody to trust, and he doesn't want it to be anyone stupid (though ultimately, the trust is given rather than earned. It's probably also worth noting that when Jack leaves town, Ames gifts him Edward's old copy of Feuerbach's book).

On the other hand, one old lady came up to Ames after the sermon one Sunday and said "Who's Feuerbach?" which, though kindly and sincerely meant, was a rebuke in the opposite direction.

That balance, needing to say something practical and beneficial while ensuring it can stand up to the strongest possible intellectual critique, is very difficult and also very interesting and, more than either of those, it is very useful. Edward was the smartest person Ames ever knew, and so he benefited from having his brother's voice in the back of his head, pressure-testing everything that came out. I am thankful, then, that I have read Gilead enough times that I have John Ames' voice, and Marilynne Robinson's, doing me the same service.

I've looked over at this and I'm a little frustrated that what I've written fails to relay the extraordinary wisdom and generosity that this book captures and communicates. I take a little comfort knowing that Ames himself has walked through similar territory. Writing about the first time he laid eyes on the woman who would become his wife, he was preaching and she came in the back, and he thought she had a look on her face that said Now say something with a little meaning in it.

"My sermon was like ashes on my tongue. And it wasn't that I hadn't worked on it, either."

1 At one point a little over ten years ago, I asked my friend Buck if we'd discussed it, but he misheard me: "Have I told you about The Iliad?" No need, Tim, that name actually rings a bell, but thanks.

One of John Ames' preoccupations in his writings to his son is the subject of baptism. It's not a contentious or theological discussion—we're not talking infant vs. adult or anything like that—but instead how sweet and wonderful to mark an occasion with a physical, tangible act. He writes about baptizing Lila (whom he would later marry), baptizing Jack when he was a baby, baptizing a litter of kittens back when he was a boy and didn't have things quite figured out yet. But there are others, too: he writes about seeing a couple on a date, smitten in early days, and the man reached up and tapped a tree branch above the two of them so that they were showered with dew. He writes about playing baseball with Edward, right after the falling-out with their dad:

"It was a dusty little street and a hot day and we were throwing flies and grounders. Edward asked a girl for a glass of water. She brought us each one. I drank mine, but he poured his right over his head, and it spilled off that big mustache of his like rain off a roof."

He also writes: "It is easy to believe in such moments that water was made primarily for blessing, and only secondarily for growing vegetables or doing the wash."

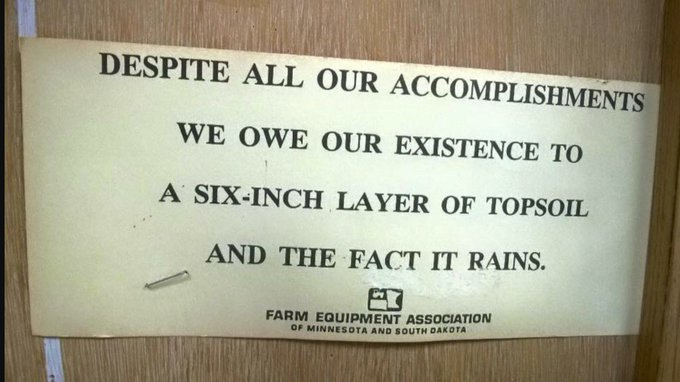

This is a very Iowan opinion to have. A pastor on the coast, where water is the means by which one earns a living, would be unlikely to say the same. And even though he puts "growing vegetables" in second place, rain after a drought serves the same functional purpose as a feast day after a fast (like Christmas and Easter after Advent and Lent), especially if you're a farmer. You're waiting a long time for something to come and it's a joyful celebration when it does.

I read Gilead this month at the same time that we started a new church, planted out of our old church, and that's been one of the main things I've been doing over the past few weeks. On the first Sunday, our pastor, Max, introduced a baptismal font, which we did not have at our old church when it met in this building. The water isn't specifically "holy water," but if you dip your fingers in and make the sign of the cross, you can physically remind yourself that you're entering a church service. You might be grumpy or distracted or whatever outside, but not in here. Time to lock in.

I love something that focuses my attention, and spaces especially. The movie theater is great at this–and, actually, honestly, the Nicole Kidman AMC ad is an especially potent example: "We come to this place for magic." I miss going into an office, actually, for this same reason.

On a related note, Max has also been working on "The Sermon Writing Machine," which sounds like an AI abomination but is in fact a dedicated computer that works offline but syncs the text input to Google Drive. When he's at that computer, he's only writing sermons. I love the focus. I envy the technology.

I don't need to hit this point that hard; I think it's pretty broadly intuitive that it's nice to set things apart in special ways. But I was glad that the water, especially, aligned so neatly with what I was reading. And it was special to use it again locking in at church this morning.

When the sitcom The Paper came out a few months ago, I put in a group chat that "I have no interest in a spinoff of the office but I do have some interest in a comedy about domnhall gleason running a small midwestern newspaper and trying to turn things around. So that's one of the things I'll have to sort out in the near future. On top of everything else"

Ultimately I did not spend much time with The Paper because it was more interested in the comedy than the news; going to it for journalism content would be like if you watched The Office because you were really into office paper sales. It's there, but nobody's top priority.

In the Wes Anderson movie The French Dispatch, by contrast, the journalism is the top priority. It uses a New Yorker-esque magazine as a container for an anthology of stories. In the bargain bin of the Books-A-Million in Ames, Iowa2, a few weeks ago, I found a book made for the movie, called An Editor's Burial, which is a collection of New Yorker articles that inspired The French Dispatch.

In the introductory interview with Anderson, he talks about how two lines made it into the script, condensed from longer concepts, and I thought both inspirations are better than the lines they inspired.

Script: "Try to make it sound like you wrote it that way on purpose."

Background: I was trying to come up with a funny way to say: please, attempt to accomplish your intention perfectly.

Script: "He was the best living writer in terms of sentences per minute."

Background: [A.J.] Liebling said, of himself, "I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better." We shortened it a bit for the montage.

I guess Liebling can also write better than anyone who writes shorter. That's what you get for trying to edit some of the best writers of the 20th century at one of the best magazines in history.

The book's great. I keep it in my car for when I'm stopped at red lights.

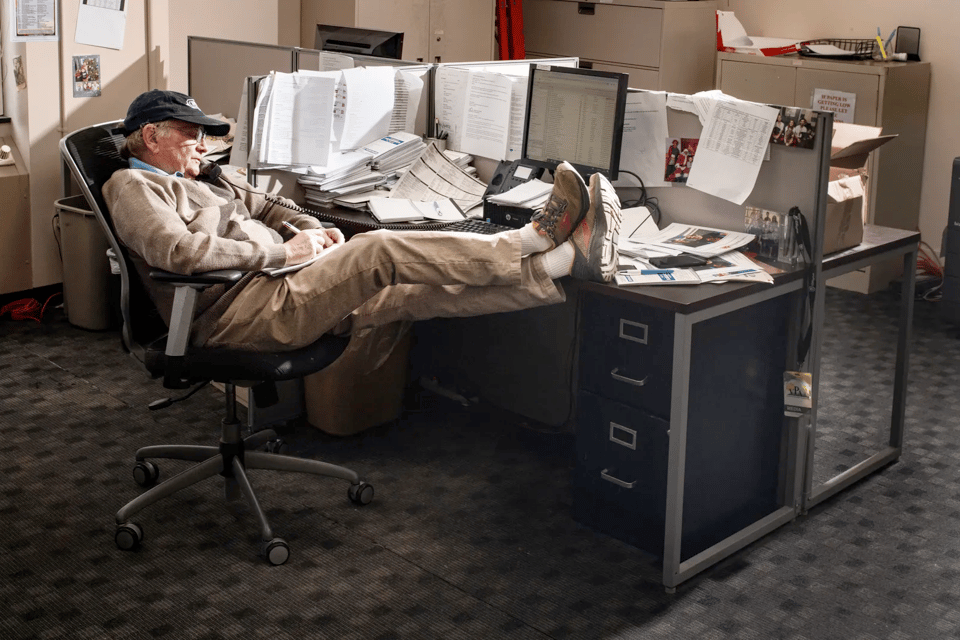

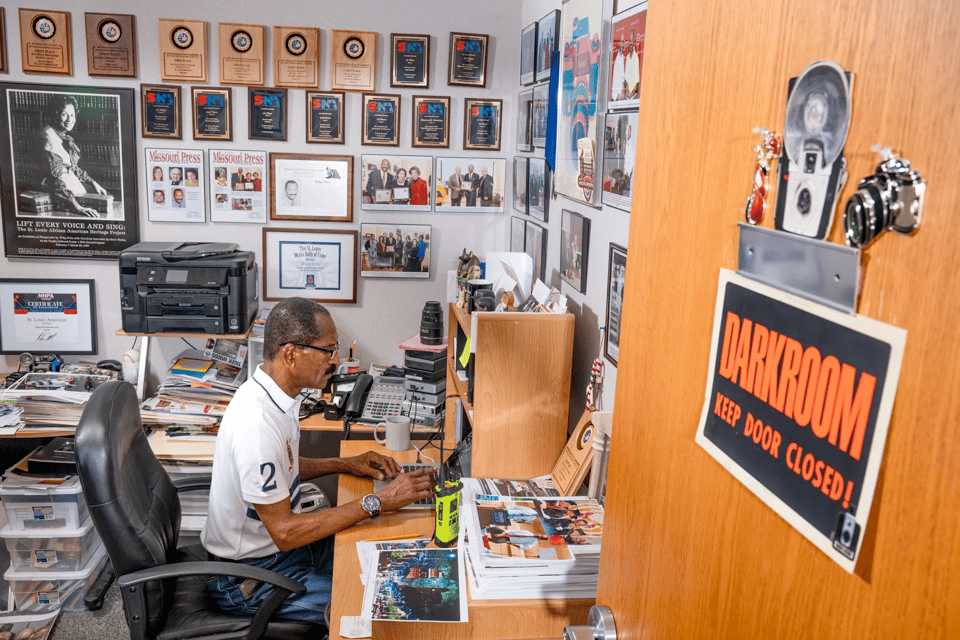

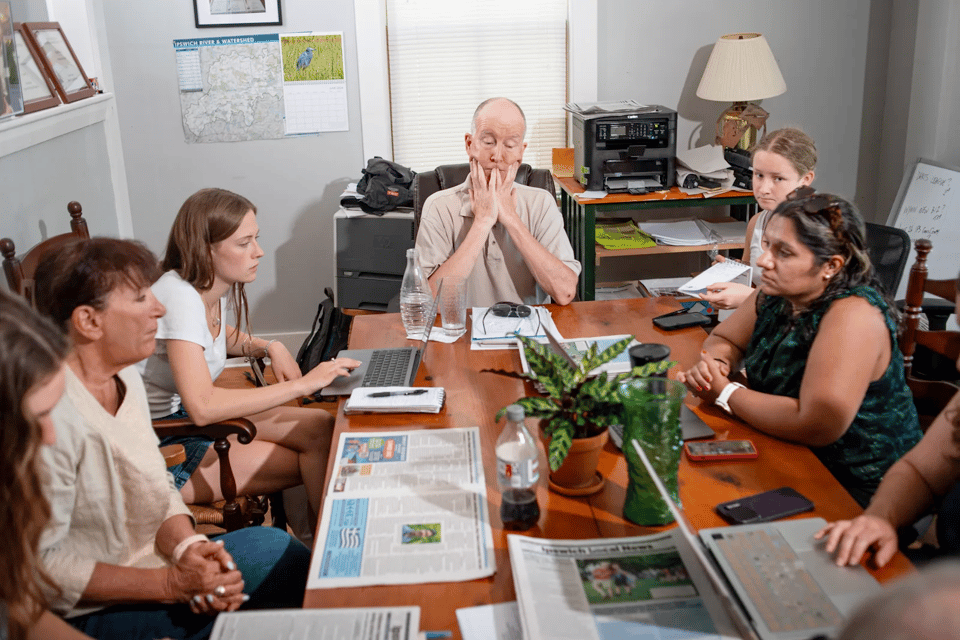

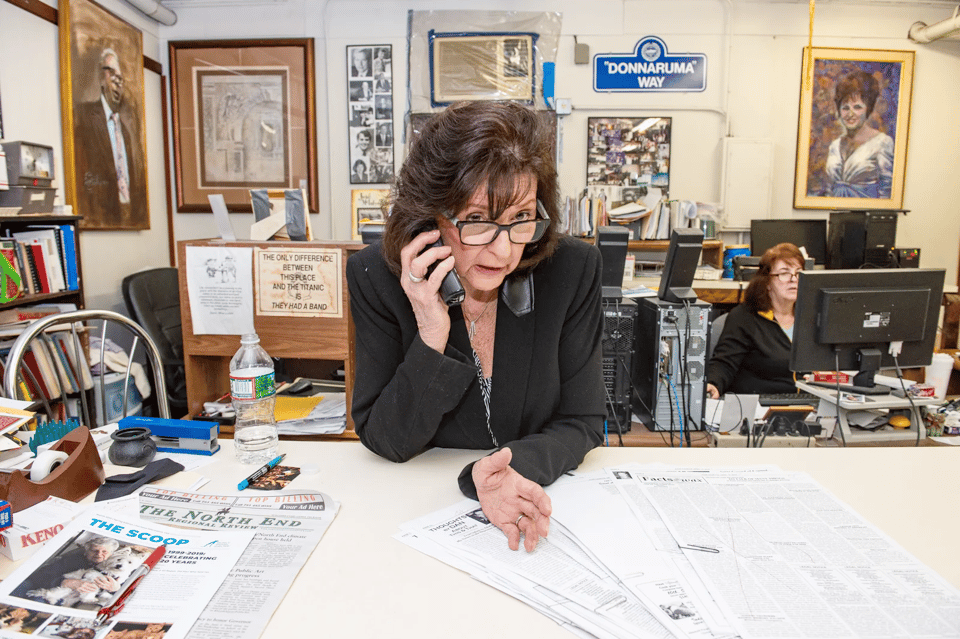

Talking about this reminds me of this photo series by Ann Hermes called "Local Newsrooms." I saw it, of course, in The New Yorker.

One last thing. My favorite New Yorker writer is John McPhee, and I just finished his book The Patch again. When I heard about Max's sermon writing machine, it reminded me of McPhee's computer from the 80s, which ran a proprietary program called Kedit, which is how he organized and structured his novel-length articles in the magazine. In his essay called "Structure," which is where he describes the function of his bespoke computer, he starts on top of a picnic table, laying and looking up, thinking about all the reporting he did in Alaska, wondering how in the hell he's going to put it all together. We referred to this so often in grad school that we just called it "The Picnic Table Problem." None of us have solved it.

Obviously we all had it better growing up in different ways; our parents bought houses, their parents, we assume, had a functioning democracy. What I consider my key advantage is that I grew up just in time to read great blog posts online, almost all of which were on websites that no longer exist anymore. Highlights include:

"Two Medieval Monks Invent Bestiaries" on The Toast, "The Sea Is Dope" on Grantland, "Decorative Gourd Season" at McSweeney's, "My 14-Hour Search for the End of TGI Friday's Endless Appetizers" on old Gawker.

The current web does not promote or economically support pieces of this genre of post and so I assumed it had gone the way of all things. Imagine my delight, then, to find a new entry just a few weeks ago:

The place where I save things I find online is called are.na, which I've mentioned here a few times before. You put things in channels, and my default channel is called "The Airlock" because it's a transitional space; ideally I move content into more specific channels later on. In practice, of course, there's just a bunch of stuff in "The Airlock." I was reviewing everything I'd put in there since the start of the year and pulled a few highlights, as well as a few common themes. This was 2025 for me.

Analog Computing

Mixed-Media Photo-Based Collage

Un-selfconsciously Wholesome Corporate Identity

White Alligators

It's really just those two, but weird it happened twice.

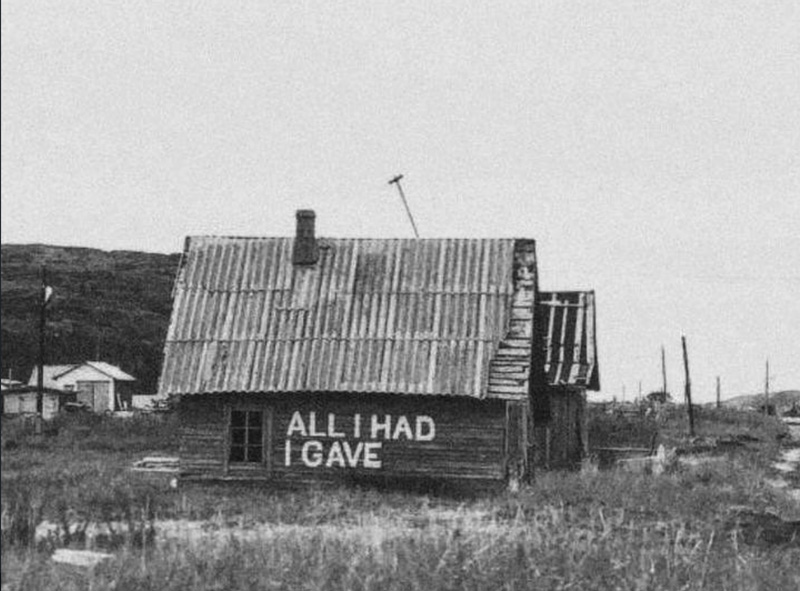

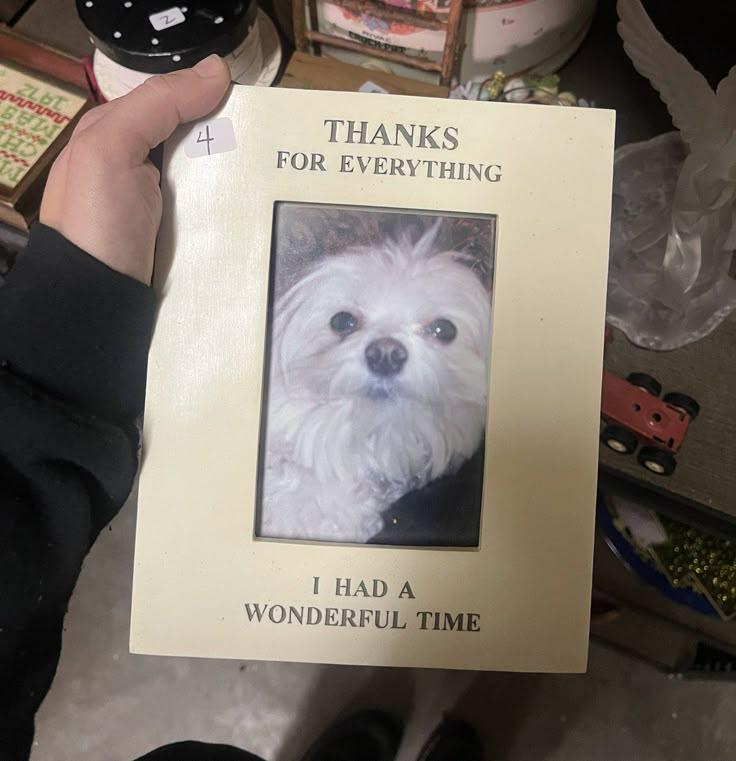

This Barn

It doesn't fit into a broader category but I wanted to make sure it was included.

The whole channel is here. Fun collection.

That's all for tonight, and for this second season of Septology, and this year, and this decade, actually. We'll meet back here with a new look on February 7, 2026, which will be a Saturday. I will have turned 30 years old.

With love from Tulsa,

Tim